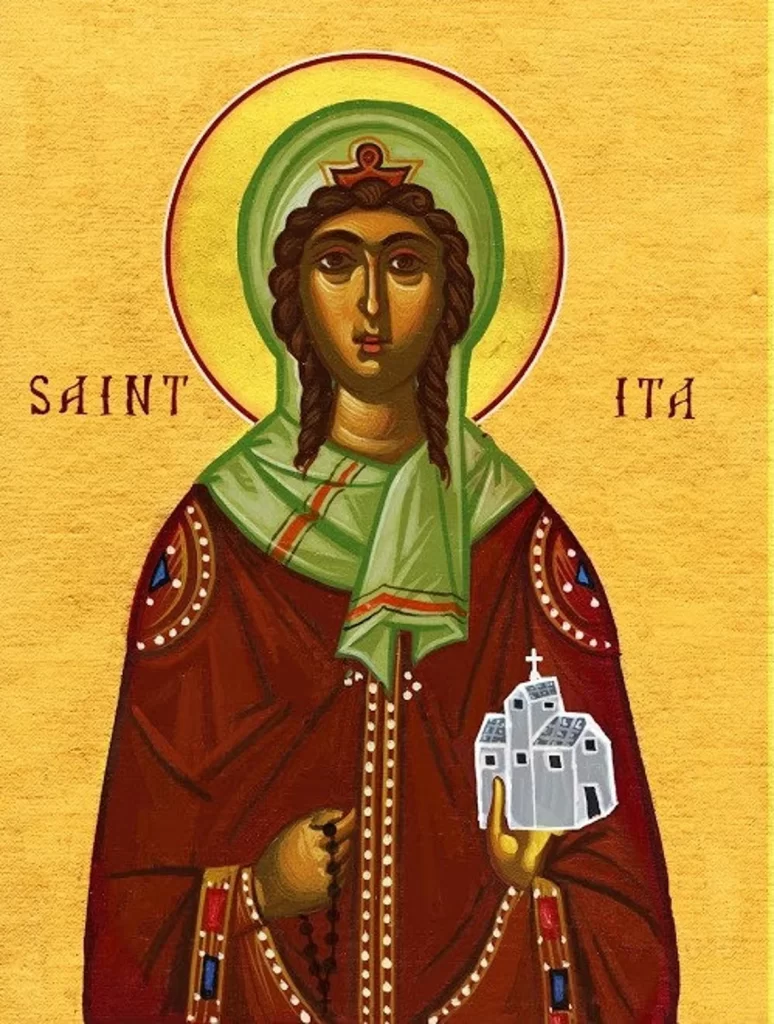

Image Source: Etsy UK

Note… you can listen to a comprehensive audio on the life of St. Ita (30 minutes plus in audio time)

St. Ita is one of the Déise people of the Waterford. Her original name was Deirdre, and she was of noble stock, growing up along the river Suir in Waterford. Her father desired an arranged marriage for her with a young nobleman. But Deirdre from an early age desired to have Christ as her spouse and serve him alone. Deirdre’s growing beauty won the hearts of many men including kings seeking her hand in marriage. Nonetheless, she always remained faithful to Christ.

Deirdre was inspired by a dream where angels gifted her with three stones, that symbolise each Divine Person within the Holy Trinity. From such a dream, she understood that she was to receive many talents and gifts from the Holy Trinity. Deirdre took the name of Ita which in Irish is pronounced Íde (Eydeh), meaning thirst for divine love, Ita was naturally gifted; helping in the affairs of her clan, and breeding horses. She also picked up on herbal medicine from her community, and applied it to the sick. She had the six virtues of Irish womanhood; wisdom, purity, beauty, musician, sweet speech, and needle craft.

St. Declan of Ardmore conferred the veil upon her. Ita would go on to Limerick and established a foundation at Chluana Credal, now called called Killeedy. This foundation was a foster school where Ita became spiritual foster mum to many noble students; for example of St. Brendan the navigator.

Many towns in Ireland can trace their names back to Íde. For example, ”Cill” in Irish means church, and Killeedy means church of ”Íde”. Another example is where Ita made another foundation nearby at Kilmeedy. The name means Church of my Íde, which is a term of endearment. There is also Kilmeadan which is taken from the Irish form Cill Mhíodáin which means church of my little Íde. Kilmeadan is a townland along the river Suir in Co. Waterford near where Ita was raised.

Along way off, in North Dublin there is a town called Malahide, called from it’s original Irish name form Mullach Íde, which means Hilltop of Íde. Now Ita had a sister too called Ína and we can trace the place name Killiney in South Dublin to Ína.

Christian Influence

We find memory of Ita in poetry; for example, Alcuin attributed to Íde the title of “the foster mother of the saints of Ireland”. Oengus attributed to her as ‘’the white sun of the women of Munster’’ in a poem written in Irish: ‘’in grían bán ban Muman, Íte Chluana Credal’’

Ita gave formation to a community of nuns, and established a school for boys, teaching them on “faith in God with purity of heart; simplicity of life with religion; generosity with love”. She learnt to build a ship, and later rebuked her former student St. Brendan for not seeking her advice on building sea worthy vessels, after he returned from his Atlantic crossing to what some scholars believe was as far as America.

Ita was a big player in converting the Druids (Draoi – pronounced Dree) to the Catholic faith. She used a sword which seemed to have divine power granted from heaven, and she would wield it at members of the Draoi. Ita wielded this divine like sword, and without touching anyone, her opponents would fall to the ground dying. This became her opportunity to preach the Good News of salvation, and the fallen draoi would forever accept the offer, and thereby quickly regain health.

St. Ita died around the year 570. We celebrate her memory on the 15th January, and this day is regarded as the last day of Christmas particularly in Limerick where she is established her monasteries.