Image taken from Aid to the Church in Need

The adapted article below is extracted from the book ”Our Martyrs” with kind permission of Damian Richardson.

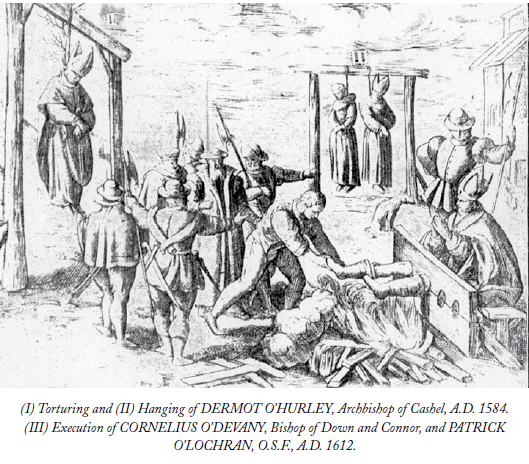

Dermot O’Hurley, Archbishop of Cashel

THE birthplace of this famous martyr was the small village of Lycadoon, in the diocese of Limerick, three miles from the city. There his parents obtained a respectable living by tilling land and rearing cattle, and were well known and much esteemed among their neighbors both in town and country whether rich or poor, and even by the chief men of that province, and more especially by James Fitzgerald, Earl of Desmond. His father’s name was William Hurley; he was owner of the estate of Lycadoon,

Founded in 1460 by Donald Kavanagh. The site is now occupied by the National Bank He was Treasurer-at-War, and Lord Justice with Loftus, Archbishop of Dublin, from 1582 to 1584. He is buried in St Patrick’s Dublin. His descendant, the Earl of Portsmouth, still holds the lands of the monastery that were confiscated.

and he also filled the office of steward or manager of the said Earl’s lands. This nobleman’s fame and power extended over the whole of the province and even throughout the entire kingdom of Ireland, though now fortune has changed and all that power has fallen away. His mother was Honor O’Brien, descended from that illustrious and most famous family of the O’Briens, Earls of Thomond, who were Kings of Munster long before Ireland was invaded. Dermot O’Hurley would himself attach little or no importance to the glory of his noble lineage.

He received a liberal education owing to the care and generosity of his parents; and after some years passed in the study of theology and canon law in the famous University of Louvain, he obtained the degree of Doctor in both faculties. Later he taught these sciences in Louvain, in Rheims, and Lille. Afterwards, having advanced in the practice of piety and devotion, the Apostolic See thought him a fit person to be appointed to rule over the Catholic of his native country. The schism as at this time raging in Ireland.

Wherefore, having been appointed Archbishop of Cashel by Gregory MIL,’ he set out on his journey to Ireland. But there was a difficulty in obtaining a passage, owing to the great dangers that Catholic merchants and sailors ran at the hands of the heretics in those times of trouble and confusion. He waited for a while in Brittany, watching for an opportunity.

‘ September 111’, 1581. There is a Latin poem on his consecration in Spic. Ossor., i.80

At length he found a bound Drogheda vessel in the harbour of Corosic. He went to the owner, and bargained with in for a passage to Ireland. There were in the port at this time other ecclesiastics from the same country who also wished to return; amongst them Nielan, Abbot of Newry, of the Cistercian Order, made earnest application for a passage.

And that all may know the great dangers which are every day run by our missionaries when going to their native country to pour out their sweat, and even their blood if necessary, for Christ and His Church, we must understand that the endless difficulties in obtaining honest and faithful men to whom the poor passengers can entrust their lives. For if either the merchant or the captain of the ship, or the common sailors, (who very often belong to other nations, Welsh, English, or Scotch people), are imbued with new errors, a rare thing in a true Irishman, the poor priest runs great risks, and especially if he is an ecclesiastic of a high position or of great learning, or even if he is merely suspected of belonging to the ecclesiastical state, as lately happened to two regulars of the Institute of the Capuchins, whose harmless manner of life and virtues are known and publicly spoken of by all not altogether strangers to the Catholic faith. These two, by their unforeseen escape from the hands of their pursuers, give others good reason for putting their trust in the divine mercy, which never abandons those who rely on it, nay, even protects with uplifted arm those who are in danger lest they may fall, or withdraws them from the risk that they may not be affrighted, and everywhere guards and strengthens them, that they may confess the name of God, when necessary, before the kings and princes of this world.

But we speak of the great and also of the manifold dangers which those, even unawares, must encounter who resolve to promote the salvation of their neighbours in Ireland. I say there is danger when they put themselves in the power of the sailors, that after embarking the ship may be wrecked, owing to treachery, the desire to betray them, or the fear of incurring any loss. There is danger on the shores of that Catholic land and elsewhere, that their landing may be notified beforehand by the spies and informers of which sea-ports are sometimes full. There is danger, too, that the guards and governors of the towns where they land may seize them and cast them into prison. There is danger on the broad ocean that they may fall in with heretical pirates, as hurtful as the Syrtes or Charybdis, by whom they may be put to death through hatred of the Catholic faith.

We see thus, the many dangers which our archbishop had of necessity to encounter when returning to this country, like a sheep going voluntarily to the slaughter. Dermot had already handed over to a certain Wexford merchant the rescript and the other documents, which showed the exalted office for which he was selected and the portion of Christ’s flock committed to his care. He was sent, ordained, and instituted by the Apostolic See, and therefore could say in all truth: ‘We have been chosen by the Lord and the Holy One of Israel, our King. He wished to send over these holy objects by the hands of others by a different way, that he might make the voyage with more safety, and that the merchants who gave him a passage might be secure from harm too.

In truth, the risks run by merchants who give passages to such persons are very great. The captain of the ship R.H., felt the truth of this. It appears that no one can enter the country, leave it, or dwell in it, without incurring danger. The Wexford merchant, who had charge of his papers, fell in with pirates; by these he was robbed, and ill-treated to such an extent that he was grateful for being left alive.

The Archbishop, having got a passage on the Drogheda ship, entrusted himself to the divine keeping, and after a fair voyage, landed at the island of Skerries. Soon after he set out for Drogheda, and while staying at an inn, there arose a discussion on religion in his presence. On such occasions he could hardly refrain from exerting his zeal and making use of his learning. A heretic who was seated by him, Walter Baal by name, which designates at once a son of the devil and a son of Belial, taking offence thereat, burst forth into insults, and very soon after rushed off to Dublin, and gave information about Dermot, filling the minds of the Lords Justices with suspicion. The departure of this treacherous guest made the Archbishop suspect his wicked purpose, and a worthy citizen confirmed his suspicion, for he secretly warned his companion and guide of the danger, that they might make haste and leave the town. This same Dillon soon after paid the penalty of his kindly office of guide by a long imprisonment, and it was with difficulty, and solely through the influence of his elder brother,” who was then a Privy Councillor, and held the office of Chief Justice of the Exchequer, that he escaped the penalty of death.

The archbishop Dermot followed his advice, and set off for the town of Slane, where that famous man, Thomas Fleming, Baron of Slane, then resided. There they were conducted into a secret room by desire of that pious heroine, Catherine Preston, the Baron’s wife. Here they remained in seclusion for some days, for they did not at all wish to be seen in public, whether at table, or meeting or conversing with anyone whom they did not know, until the plot laid by the traitor, Walter Baal, should be baffled and the report that he had spread abroad should cease.

(Sir Lucas Dillon. Queen Elizabeth used to call him her faithful Lucas, and rewarded him well for his services. He is buried at Newtown, near Trim. See Archdall’s Peerage, iv.155)

When they thought they had escaped from him, they began to act with more freedom, to sit at table at the usual meals, to enter into conversation with those whom they met, to join the family circle, and they were not afraid to be seen or to speak with any guests that came the way. It so happened, whether by accident or on purpose, that Robert Dillon,’ one of the Privy Council and Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, came to the house. While they were seated at table, the conversation turned on some important topic which gave rise to a warm discussion, and in the middle of the dispute some words which showed his learning fell from the Archbishop’s lips; these made the cunning Chief Justice, though he had a squint in one of his eyes, and was totally blinded by worldly ambition, mark the man carefully, and ask who he was, where he had come from, and much more, all of which he treasured up in the depths of his soul until an occasion should offer of putting it before the chief Governors and the Council. He mentioned the facts, and at the same time suggested a plan for bringing the Archbishop from his place of concealment to answer for himself before the Council of Kingdom ; if he had fled from the place, he said his suspicions were not lessened by the flight, but rather strengthened, and in that case the Baron himself should be called before the Council to answer for him, or should bring him to them. As a fact, he had fled. The Baron was brought before the judges, and bitterly rebuked for having admitted into his house a wicked man, a rascal, a traitor, a disturber of the public peace; for having allowed him to sit at his table, and for having kept and supported within the walls of his house one who was a canker of the state. He should be mulcted in a heavy fine and long imprisonment, or he should bring to them the Archbishop, wheresoever he had concealed

himself. The Baron, frightened by these threats and in a state of great terror, immediately went off in search of him. This man, wholly taken up by the cares of this world, and lukewarm even then in his faith, and not at all earnest in his zeal for religion, though he could not save himself and his property in any other way, especially as his persecutors displayed such fierceness and threatened him with the severest torments.

Wallop’s colleague, Loftus, did not thirst for the blood of the innocent man to such an extent ; he was rather inclined to mercy and moderation, for by nature he was more gentle, as became the Chancellor of the kingdom, who had to decide what was right and just; but the other, who shared the government with him, was a disciple of Mars, and trained up in the arts of Bellona rather than in those of Pallas, blood-thirsty and fierce, and could not be appeased or satisfied unless blood was shed. An ill-founded suspicion haunted his mind in reference to Dermot, that he had a knowledge of, or took part in, a process which had been carried on shortly before at Rome or Madrid against a nephew or other relative of his, who had been accused by his countrymen of reviling the Catholic religion, and had been handed over by them to the tribunal of the Holy Inquisition to be punished or censured. It was said commonly that the decision in the case fixed a barb in his soul, which he thought could not be removed, or the wound inflicted by it healed, in any other way than by the executioner blunting it or covering it with blood in the body of the martyr. As the judges knew this well, they warned the Baron to make a careful search, and to bring Dermot to them if he wished to save himself.

(Sander says Nicholas. Baron of Slane, had been imprisoned several times for the faith. De Visib. Mon., p. 672)

(Then Protestant Archbishop of Dublin. See Moran’s Archbishops of Dublin, p.108. He and Wallop were Lords Justices then.)

The Baron of Slane, who thought more of his own safety than of that of his friend the Archbishop, set off in pursuit of the flying lamb, I do not say like a wolf or a hound, but rather as an active hunter. He overtook him’ at Carrick, on his return from a pilgrimage to the Saving Wood of the Cross, which he had vowed some time before, when he was in danger of shipwreck, to make as soon as he landed, and in very civil language suggested to accompany him to Dublin, that he might appear before the Lord Justices, prove his innocence, and make it evident to everyone that he had come to Ireland in a truly ecclesiastical spirit and through zeal to preach the Gospel.

What was the pious Bishop to do? He was not concerned about the risk to his own life, and he wished to save the Baron. Thomas Butler, of pious memory, the famous Earl of Ormonde3 was then at Carrick. He loved Dermot, and revered his virtues and exalted office. He ordered food and other necessaries of life to be supplied from his own house to Dermot clandestinely; some even say that he was privately called in by the Earl to give the sacrament of confirmation to his son James, born a short time before, who died at an early age in England.

The unsuccessful rising of the southern nobles was crushed just at this time. The Earl of Desmond, now that his forces were few in number and his strength much impaired, was looking for a hiding-place, for there alone could be hope for any security.

The Archbishop travelled with the baron the different stages of the road to Dublin. But while the Baron stayed at the public inns or was sumptuously entertained by his friends, the Archbishop’s halting-place was the public jail, for this was thought likely to hold him more securely. It happened that one night during the journey he was confined in the prison at Kilkenny.

When the Archbishop reached Dublin, he was brought into the presence of the Lords Justices, and examined in great detail by the Council. Though he was accused of many crimes wrongfully, which were neither proved against him nor true, he showed he was free from all guilt. Adam Loftus, the Chancellor, dealt with him in a kindly manner, and by setting before him many temptations, tried to persuade him to conform, as they call it, and to accommodate himself to the customs of the present time. Henry Wallop addressed him in a savage manner, and reviled him in abusive language with many insults and threats, and his inveterate hatred against the orthodox creed could not be appeased otherwise than by the murder of this victim, whom he marked out by his looks and in his thoughts for slaughter.

Though he was examined at different times, yet not the slightest proof could be given of the charges made against him. He thus could not be convicted by open trial. Since Dermot O’Hurley was also not subject to English law, and he could not be proved guilty by judicial process in his native country, a new system of trial was devised against him, that there might be no means of escape from the fangs of the cruel executioner. They resolved to have the peaceful Bishop put to death by military law. But first the archbishop should be subjected to torture, so that even if no confession of crime could be wrested from him, he should be forced by the intensity of his sufferings to abandon the Catholic faith. But the cruel tyrant was disappointed in the case of Dermot. The fire of the love of Christ could not be overcome by torture.

Fortunately a certain noble and learned man, a citizen of Dublin, we can learn from eyewitnesses what he writes as he describes them in detail. The Archbishop of Cashel met with a far more painful death indeed the blood-thirsty cruelty of Calvinism may be seen from this one act of barbarism.

(Stanihurst, Brevis Prmunitio, p.29)

‘’ The executioners placed the Archbishop’s feet and legs in boots filled with oil, they fastened his feet in stocks, and they put fire under them.’ The oil, heated by the flames, penetrated the soles, legs, and other parts, torturing them in an intolerable way, so that pieces of the skin dropped from the flesh, portions of the flesh from the bared bones. He who was presiding over this torture, not being used to such strange cruelty, rushed hurriedly out of the room, that he might not look further at such savage conduct or hear the cries of the innocent Archbishop. The Calvinistic executioners wished to gratify their minds for a while with these strange cruelties, but they did not mean to be satiated thereby, for after an interval of a few days they hurried the Prelate, who had been racked and was almost expiring from the continued tortures, and had no thought then that he should be put to death so suddenly, to a field not far from Dublin Castle, at the break of day, lest the citizens should crowd to witness such cruelty, and there they hanged the innocent man from the gallows with a halter roughly made of twigs, that his sufferings might be all the greater. Whilst they were gratifying their innate love of cruelty, the blessed Bishop taken to the heavenly fountain of eternal life, is victorious though conquered, though he was slain he lives, triumphing for ever over the cruelty of the Calvinists’’.

In the cries of the Archbishop of which I speak there was only the pious outbursts of a Christian soul which felt the bitterness of its tortures. For he was a man of sorrow, and acquainted with infirmity, and from the sole of his foot to the crown of his head he was in torture. Not only his feet and legs were penetrated by the hot oil and salt, not only did the skin and flesh fall from the joints, not only were the muscles and nerves, the veins and arteries, saturated with the fiery mixture, not only were the limbs and sinews and bones pierced by this fierce fluid, but his whole body was devoured by the heat, and at the same time bathed in a cold sweat.

(O’Sullevan says he was tortured in this way for an hour. Hist. Cath., p. 125)

With a loud voice he used to cry out: ‘Jesus, Son of David, have mercy upon me.’ These words he uttered aloud he repeated and pronounced sweetly, ‘Son of David, have mercy on me’; and the raising of his voice with the elevation of mind was joined with the sweet harmony of his virtues. The victim was stronger than his tormentors, and that loving faith, that purity of religion, that brightness of the orthodox light, could not be extinguished or dimmed by the penetrating salt or the burning oil.

He seemed to be exhausted by the extent of his sufferings while he was fastened to the stocks; he was speechless and senseless; he lay on the ground dumb and almost lifeless; he could not move his eyes or tongue. his hands or feet, or any member of his body. He who was superintending the execution began to feel uneasy, and to dread that while ordered only to inflict torture and apply the fire, not to kill, he had exceeded his orders and brought about the Archbishop’s death. In great alarm, to avoid the guilt of killing him by the torture, he wrapped him up in linen and laid him on a bed of down, and poured a few drops of cordial into his mouth, to see whether there remained any feeling still in his tortured body, or the breath of life could be recalled. The following morning, as he had recovered a little, a drink of aromatic extracts was given to him, that he might be strengthened to endure new torments; and when he swallowed some of it from the spoon, his tormentors showed relief.

Our martyr was visited in prison by Charles MacMorris, a priest of the Society of Jesus, then in Dublin. He had a knowledge of medicine and surgery, and in return for cures effected on some noblemen, he had been released from prison, into which he was cast on account of his faith. By him the Archbishop was supplied with medicines and food, and at the end of a fortnight he was restored somewhat so as to be able to sit up, and even to limp about a little.’ His enemies tried to make him waver in the faith. High positions, even one of the chief offices of the kingdom, were offered to him if he would resign the office of Archbishop which he held, renounce the primacy of Rome, and acknowledge the Queen’s supremacy, both secular and ecclesiastical. Among others sent to question and tempt him was Thomas Johns,2 now Chancellor of this kingdom. But he remained firm as a rock, though the waves roared around him. His only sister, too, Honora O’Hurley, was directed and instructed to offer him a new temptation. And she earnestly besought him to yield. But, with a fierce look, he bade her kneel down before him, and humbly ask pardon for so great a crime against God, one injurious to her own soul, and odious and humiliating to her brother.

These Governors were soon about to resign their office, to be succeeded by Sir John Perrott, who had just come to Dublin. Before he entered on his office, word was brought to them that the Earl of Ormonde was coming in all haste to Dublin to welcome the new Viceroy and interpose on Dermot’s behalf. But the ferocity of Wallop could not be appeased or satiated except by the death of this innocent man. Wherefore, as Perrott was about to receive the sword of office on Trinity Sunday, and as their authority ceased when he entered on office, lest their successor might turn out to be too gentle towards the innocent man, on the preceding Friday, and at early dawn, as we have already said, he was put on a hurdle and taken out by the garden gate to the place where he was hanged, Wallop himself leading the way, as the report goes, with three or four of his guards. There he was hanged with a with; tough, flexible branch of willow, used for binding, or basketry. While they hanged him the archbishop prayed to God and forgave his tormentors from his heart.

He was taken out of the Castle without any noise, that there might be no disturbance in the city. The Catholics who were imprisoned there, seeing what was taking place, cried aloud that an innocent man was going to be put to death. The holy martyr was hanged in a green’ near the city. After he had breathed forth his blessed soul, his body was buried by the heretics in the spot where he was executed. William Fitzsirnon placed it in a wooden coffin and removed it to a place of safety. Saint Stephen’s Green, as an old tradition says. The Green was then outside the city. The spot where he was put to death was, very probably, where Fitzwilliam Street crosses Baggot Street. This was the place where executions took place up to a comparatively late date.

Towards evening it was buried in the ruinous chapel of St. Kevin, which is close by.’ Many miracles are said to have been wrought at this tomb, and in consequence the old church has been restored, and a road has been opened up for the people who frequent the place in great numbers, and are wont to commend themselves to the intercession and prayers of the holy martyr.

There is confirmation of the first part of Rothe’s narrative in a letter written from Paris by two Irish priests, in the interval between the first time O’Hurley was put to the torture and his death, to Cardinal De Como, Cardinal Protector of Ireland, written by Fr. William Nugent and Fr. Barnaby Geoghan”

Some Protestant writers denied the O’Hurley incident of torture. They have written their propaganda.