Image source: Catholicireland.net

Material distilled from St Aengus parish and Catholicireland.net

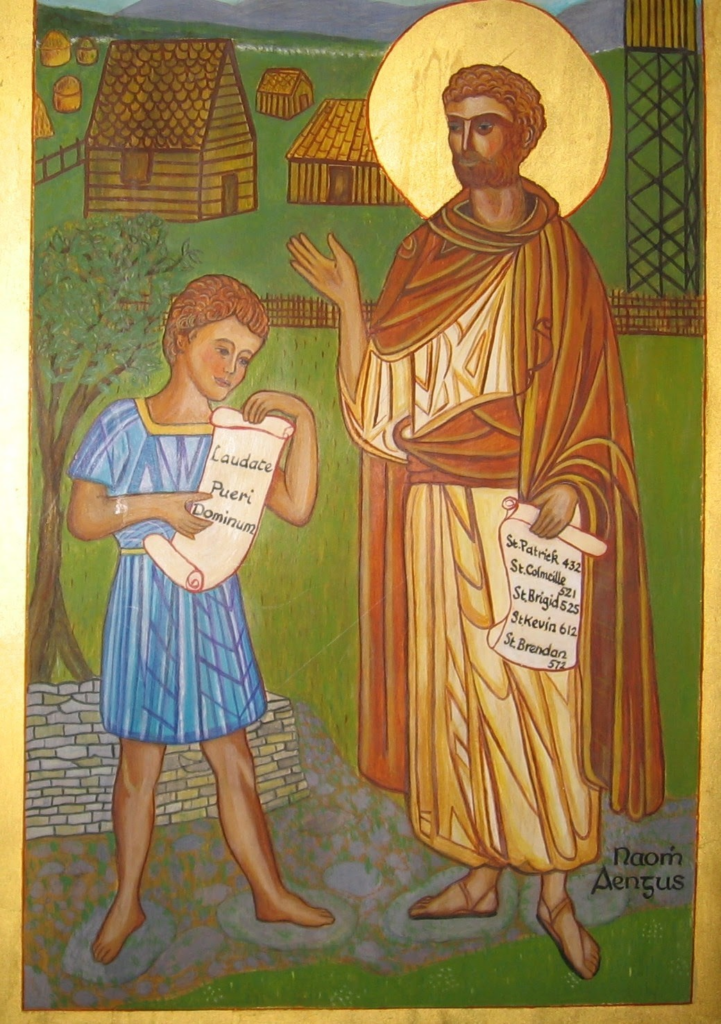

St. Aengus lived around the 8th and 9th century. He heralds from Clonenagh, Co. Laois. His family, were from the stirp of the Chiefs of Dalaradians in Ulster’s North East. Aengus went to monastic school close to present day Mountrath, under the direction of St. Fintan.

He lived as a hermit, at Dysert-beagh by the banks of the river Nore. The word ‘’Dysert’’ from the original Irish ‘’An Díseart’’, meaning hermitage. At his small hermitage, Aengus grew close to God, through an austere life & solitude. In his prayer life, he experienced the presence of Holy angels. He moved and built a hermitage a little further away from his original one in Clonenagh, and settled in a more isolated placed near Maryborough called Dysert-Enos, which takes its earlier Irish form for Hermitage of Aengus.

He loved the solitude, and the austere life, feeling the benefits of being close to God. But he also gained a big following. This raised a great challenge to his life of solitude, as he was constantly interrupted by a stream of visitors. He therefore abandoned his new hermitage and went to live discreetly as a lay brother in a monastery in Tallaght, south Dublin. St. Maelruain was the abbot, and he was unaware that Aengus was in his midst, as Aengus did not reveal his true identity.

But Aengus was found out with time, as his qualities were so good, that it became evident that the stranger was someone of note. This came about one day, when Aengus went to assist a young monk student during a particularly challenging lesson. Upon the discovery of the very gifted ‘’lay brother’’, Maelruain collaborated with him to produce the “Martyrology of Tallaght” in 790 A.D, which gives the oldest account of the Irish saints.

The two monks became known as for their spouse of God movement, hence they took on the Irish title, ‘’Céile Dé’’ or culdee in English. As founders of the Céilí Dé movement, they refined a spirituality seeking a purer and more austere monastic life. St. Aengus went on to produce his notable ‘’Feliré’’, which poetically celebrates the saints of Ireland, and was inserted into the ‘’Leabhar Breac’’. The ‘’Feliré’” is one of the primary sources of information on the early Irish saints. After St. Maelruain passed away, Aengus returned to Clonenagh as Abbot and bishop, and remained at his Dysert-beagh.

St. Aengus passed away on Friday, 11 March, 824.